A short story:

“At the Heart of the Matter”

“At the Heart of the Matter” is a portmanteau short story.

What ties together the three parts is their relationship to me and people in my life.

But overriding all that, there is a connector beyond family and friends; beyond what life throws at us chronologically and what we sometimes think we are able to do.

What makes us different, in fact, from everything else.

This, then, forms part 1 of an autobiography in three parts.

On this page we find the short story, which forms that first part.

Part 2 is the diary.

And part 3, only very recently written and posted first on my feed at LinkedIn, completes the job I set myself a while ago, not terribly consciously I have to admit, to tell my version of the events of my life: being, surely, mine as much as anyone’s.

Surely that …

“At the Heart of

the Matter”

a short story by mil williams | contact@qcdocu.com

I remember what happened in a curiously distracted manner. It’s almost as if I’m choosing not to remember. Impossible not to remember, though.

Impossible to forget.

Three moments in my life. Three moments when the world seemed to collapse around me. Three moments when I would beg to differ. No. Not a wonderful life at all. But at the heart of the matter, there is this abiding truth: whether we differ or not with what life has in store for us, we have no alternative. We must fight.

So is this a story of battle? Is this a story of war? Is war an appropriate metaphor? Can life ever mean an entire absence of peace, ever limit itself to a cruel persistence of vision?

You see, I was brought up to believe in the story of good versus evil. I was brought up to believe in truth. My mother is a Catholic. My father is an atheist. They are both believers in their own very different – and yet oxymoron-like – ways. There was so much belief infusing my childhood, like a sharply smoked tea of distant origin. I was a membrane of the basest kind. Osmosis was my learning curve, my education, my tool. I refused to ask questions – for the answers seemed obvious.

“What do you mean?”

“Can’t you see?”

“Not again!”

“Yet another thing to do …”

So that’s why only the questions seemed hard. But the questions always are.

*

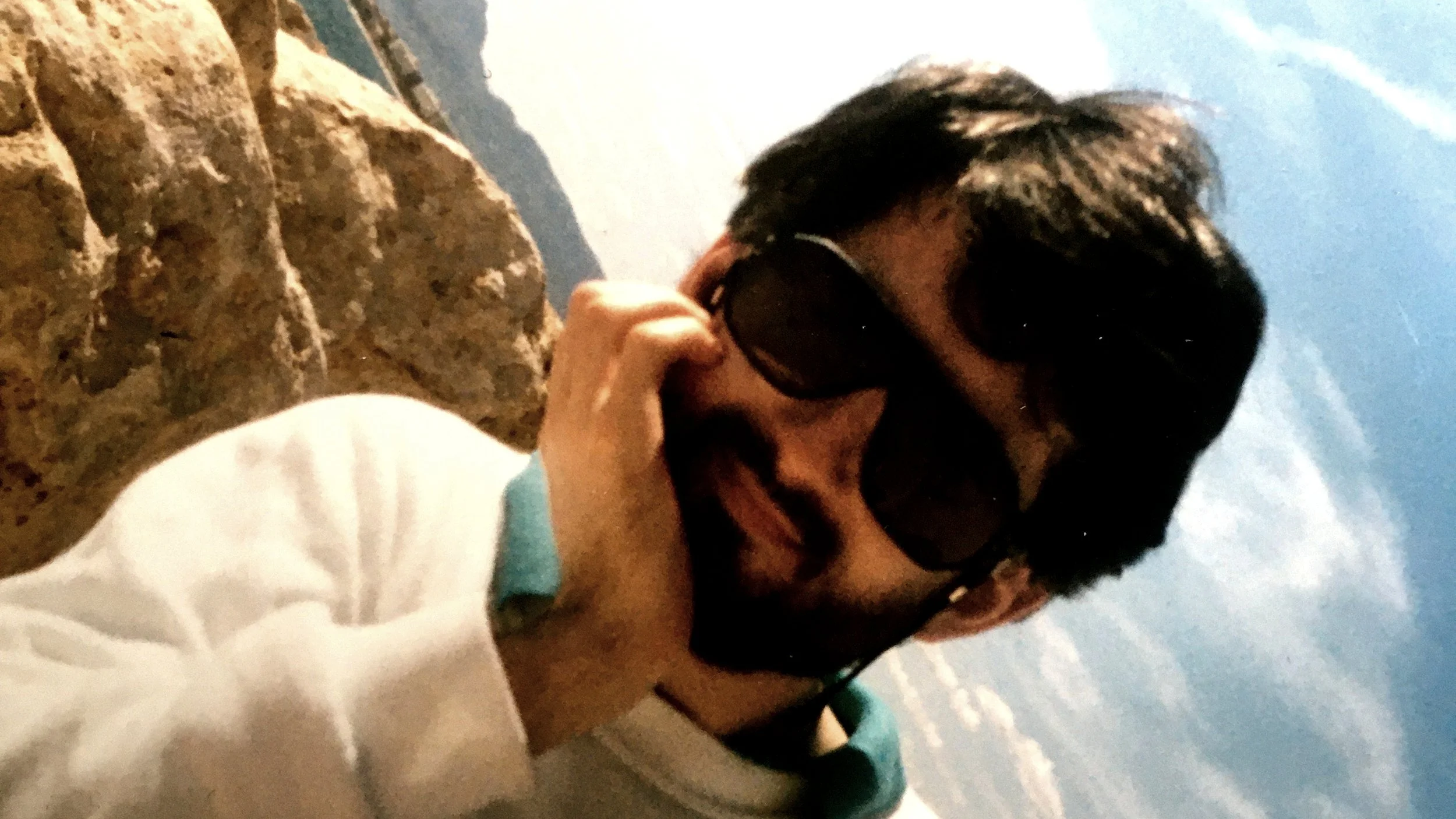

It was 1992. War had reached Croatia. I was living in Spain. The city of Burgos, in fact. A beautiful city. Running through its centre like a peppermint stripe through a stick of northern rock was the verdant río Arlanzón. Its banks were cloaked in a thick meadow grass, sprinkled and cut back regularly to ensure perfection where nature resisted.

Modern men and women strive so violently to tame what is beautiful, untamed.

Burgos is a place of hot summers coupled with cold evenings that, even in the middle of August, require one to wear a jumper. A hardy people, los burgaleses.

Over one winter to visit, I remember my brother observing that in Burgos young women wore not short skirts but – rather – long belts.

A determined people, in fact.

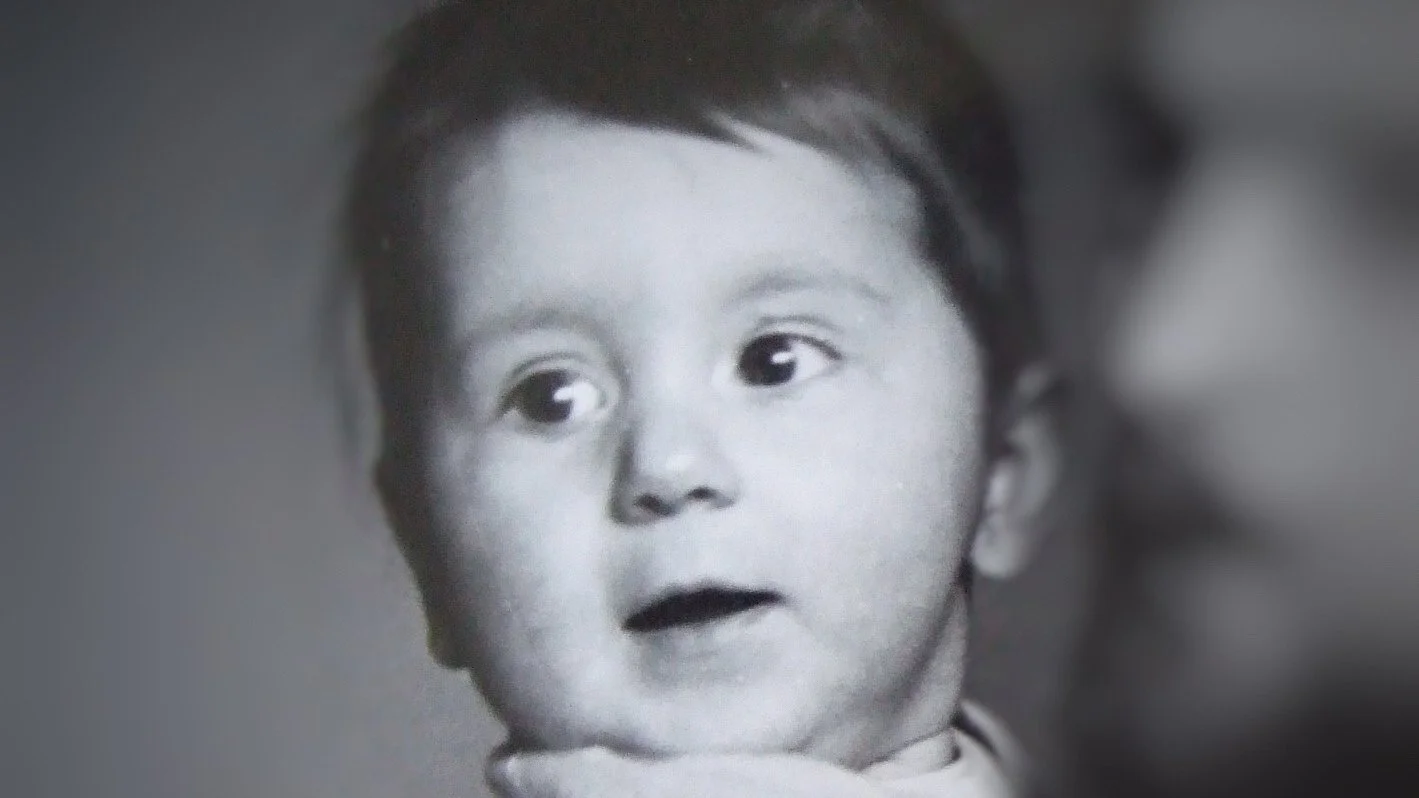

My wife had a shortwave Sony. And so it was that I could listen to the BBC news as I sat at home with our one-year-old son. I was bereft of any understanding, any useful comprehension, about what was happening in the country my mother came from. Yes. It’s very true. We forget the things that hurt us and remember only the good, but the good we remember doesn’t really affect us – it’s only the things that hurt us and cause us pain which ever really hit home in the end.

We think we are able to ignore them but at some point they will jump up like a mental cobra of the soul and frighten us – as they surely should.

(Even a wonderful life is like that and, as I have already pointed out, mine has not been a wonderful life.)

And so it was that I was frightened. I am sorry to say, as I listened to the news, to the abandonment by the West of small countries which – a priori – should’ve known better (small countries which had no oil or other natural resources worth fighting over or defending), that I cried in the presence of our son on more than one occasion. He would not know why I am sure. Or perhaps he would. He now wants to work for the diplomatic service. Perhaps, in some small way, the injustices of that time have informed his understanding of the world.

Perhaps, in some small way, everything that goes around does indeed come around.

Perhaps, in some small way, justice can be done. Even if it must never be seen to be done.

So he cried and I cried. He cried because he was a baby and I cried because I was a man. He cried because his body didn’t digest his food properly. I cried because I couldn’t digest the news properly. At the heart of the matter, it’s not the heart that counts. At the heart of the matter, it’s the head. It’s heads that are turned and heads that turn the heads of others. A smile from afar is a cold beast – matter-of-fact and to the point. It’s only in close-up that a smile warms us up. Then it’s the eyes, not the mouth.

Then it’s the head that counts.

I can count the ways I fell in love with you.

Not because they are finite but, rather, because they are innumerable.

I fell in love with my wife and we got married.

Then in our third year of marriage, just as war came to Croatia, just as I couldn’t stop crying in the presence of my son, she came home one day with a simple headache and a box of paracetamol.

I do remember walking back with her from her school that day. Funny, isn’t it? Perhaps, in truth, the secret to living life is knowing when a bad thought is actually one you need to learn how to love, for – maybe – the Lord believes it of use.

It was a hot day. A sunny day. A Monday, I think, as the fishmonger’s was shut and in Spain – at least at the time (I don’t know now; it’s been a while you see and things change as time passes, they change so very much) – the local fishmonger’s was always shut on Mondays.

It was a strange headache. It kind of hurt round the back. She went to bed at midday. She never went to bed at midday. She never went to bed unless it was night. Midday was for dozing on the sofa, after lunch; after the 3 o’clock news. Midday was unheard of. That’s why I was frightened. I wonder – now – what our son was feeling at the time. Though still mainly unable to speak, he was also at the time unable to entirely misunderstand what we were saying to each other. What we were doing to each other.

A strange headache it was. Round the back, round the neck, round and round in circles that tightened.

She was in hospital by late afternoon.

The diagnosis was severe. Bacterial meningitis. The severest form of all, in fact. It really did seem too much.

And now my memory of how it felt begins to fade. It’s affected me for sure. I’m convinced that it’s still deep down there, waiting to jump up and strike me when I least expect it to, when I least need it to; or, maybe, essentially, in my lapsed and only ever partially infused belief system, when the Lord feels it may be most useful for me.

What do I know?

Why should I care?

Tell me that, at least.

Life seems, quite insubstantially, to be a series of random events that generate fear and apprehension in small beings of little relevance. And we spend most of our time trying to shape these events, even as we cannot; we spend most of our time trying to achieve a certain relevance that we can only ever define in terms of what we ourselves – quite futilely – judge to be fine. What we ourselves judge to be wise. We determine the rules of the game so that we can achieve our goals. But – in the mad rush to achieve this relevance – we forget how navel-gazing being judge and jury can be. For that is all we are. Judge and jury. And that is nothing.

There is no virtue at all in defining what defines us.

*

She survived of course – but only because she’d suffered meningitis on two previous occasions, and had, in time (though not plenty of time), been able to recognise the symptoms.

“Two previous occasions?” you ask.

Well, indeed. There must be more to the story than that. And, of course, there is. After a certain and stiff period of recovery and antibiotics, it was revealed that the runny nose she seemed perpetually afflicted with (the runny nose which meant she went through as many Kleenex a day as those gorgeously sexy cigarette packets of black tobacco that almost everyone of any, even feigned, relevance seemed to smoke in that decade) was actually the liquid that was supposed to protect her brain from knocks and bumps. She had a hole in her nasal cavity. Congenital, almost certainly. Deadly, without a doubt. A multitude of earlier x-rays had failed to show up what the modern technologies of magnetic resonance discovered. When the man at the clinic in Palencia gave us the results, he smiled sadly. It was such a sad smile.

I remember the sadness in the smile you see. Even as I say I remember only the good; but, if truth be told, as I recount the story, I also remember quite a lot of the bad.

I wondered, afterwards, on the journey back in the ambulance to Burgos, what that smile meant. I didn’t say anything to my wife.

What can you say?

The surgeon then said we’d need to do a biopsy.

Biopsy?

Why?

Don’t we do such things for cancers?

Just a test we were told.

Doctors sometimes do the sorts of things we ourselves choose to do.

Is that because they’re human too? Is that because they can’t help getting involved, even as they know they shouldn’t?

So I suppose you want to know what the result was. Well. No cancer, actually. The sad smile from the man in the clinic in Palencia meant nothing in the end. A trailing thread of brain cells that hung down into my wife’s nasal cavity – probably all her life – was the route that infection had taken three times in her life. And the surgeon said the solution – yes, the solution – was a rather dramatic operation. He put it in simple terms. She could ignore what had happened and wait for it to happen again. And for sure, sooner or later, it would happen again. Or she could decide to have the operation.

So it was that I encouraged her to have the operation. I have a general and overwhelming belief in high-technology medicine, though, as you may gather, I find it difficult to believe in God. Yet, the former requires one to put one’s life in another’s hands even as the latter makes no greater demands. Why do I believe so easily in the tools of God where believing in God Himself is so very, very hard?

But I am digressing.

“The operation?” you say.

Aparatoso is the Spanish word the surgeon used on at least one occasion. I suppose “complex” is the most appropriate translation. But the word aparatoso is also used to describe multiple pile-ups where no one gets hurt. Is that what an operation means? Is that what medicine is all about? Is medicine always a series of accidents waiting to happen? Is medicine, actually, like so much of modern life, a question of apparently accidental wisdoms which actually reveal our greatness, our ability – in the face of insignificance – to soldier on into the future?

“The operation?” you repeat.

The operation? This is how the surgeon described it to us. It involved peeling back the skin from my wife’s forehead from under the hairline to avoid visible scarring, drilling a hole through the skull on the left-hand side to allow for access, glueing the congenital defect with something the surgeon described as approaching a medical form of bog-standard super glue, and then putting everything back together again, much as Humpty Dumpty might rescue a kingdom.

In that description we have the full horror and awful wonder of our ability to soldier on into the future.

We had to wait for two weeks as my wife recovered from the meningitis itself.

In the meantime, I would sit at home and look at my wife’s dainty slippers and remember what it was like when we first met; and remember the times we went out for drinks and the times we spent walking through a park and the coach journeys from Burgos to her hometown of Salamanca; and fighting with my mother-in-law and trying morcilla de Burgos for the first time and visiting friends in Navarra and the sound of the street in the early morning; and the time we holidayed in Croatia and the time we were rained out for two weeks in Llanes and the good friends I made and then later the good friends I lost. And if my son was about, I would not cry. And when my son was asleep, I would sob quite uncontrollably.

So we went ahead with the operation.

And the operation was successful.

And the patient survived.

It took six months for her hair to grow fully back. It took years for it to lose its initial spikiness.

*

Yes. Reading back on this, it seems I remember rather more of the horror than I expected. If the outcome had been different, perhaps I would have chosen to remember differently.

At the heart of the matter, it’s the head that counts.

*

Over the next decade, I tried to set up a training empire and failed, lost money which didn’t really belong to me – or, at least, wasn’t mine to lose – and made and lost some very good friends.

My life lost her job too.

We had to retreat from Burgos to Salamanca. We lived there from 1999 to 2002. We retrained and decided to pick ourselves up and brush ourselves off. We were going to do so many important things. We were shaping events, giving them a form, creating content, writing a narrative.

We were doing what all human beings with a little time to waste try and do.

We were playing games.

We were children again.

It’s so much easier to be a child. Time doesn’t hang heavy as yet. Except in the sense that sometimes it’s too slow.

Not like being a grown-up. When you’re a grown-up, time simply flies past. The less you have, the faster it gets. Time is not exactly elastic. It doesn’t rebound. For at the end, it simply snaps.

But at the heart of the matter, it’s the head that counts. And just as we were on the point of setting up an online publishing company, my mother-in-law, the one I always fought with, the one I could blindly see no virtue in, the one whose own mother had accused me of stealing her granddaughter away, the one who was invincible, the one who intervened in every act and family decision, the one who cooked so well, so completely, so correctly, so inviolably, the one who worried so much, the one who consumed Aspirina (but only the branded version) in much the same way as some children eat chucherías … well, she intervened once more. She intervened in a way no one could ever have foreseen.

She died.

She took six months to die. In the meantime, of course, she had space and room to organise her affairs. She bought each of her children a new car. We continued to go out for meals. Towards the end, she sat in a wheelchair. She needed help to eat. She was losing control of her bodily functions. Her speech was getting slurred.

She still sat at the head of the table.

At the head of the table is where it counts.

But she didn’t count any more.

She didn’t even know she was dying.

The family decided not to tell her. The doctors concurred.

Till the end, she thought it was a cyst in her brain. Till the end, she was completely unaware of the implications. Till the end, invasive brain cancer was simply not on the cards. Thus it was that her family were unable to say goodbye. They didn’t say goodbye. They couldn’t. When they could, it was too late and she was incapable of understanding the words. I wonder, now, if my son didn’t understand more when Croatia went to war and I cried him to sleep and watched my wife’s slippers sitting emptily at the end of the bed.

So my wife’s mother (sounds better than mother-in-law; sounds kinder) died of brain cancer just as we were planning to pick ourselves up and dust ourselves off.

My wife felt cheated. Years spent back in Salamanca had led her to the point of beginning to truly communicate with her mother. Things were on the point of being said; important things.

Not entirely generous things.

Now her mother was dying.

Now it was too late.

It wasn’t our decision not to say goodbye. Even that decision was taken out of our hands. Can you imagine what it is like to watch someone die for six months, to visit them every day, to perceive a daily deterioration – and never tell the truth? Can you imagine, at all, what living a lie for six months can be like? Everyone except the object of the lie knowing exactly where reality lies – and not saying. Not expressing their innermost feelings. And feeling that, in so doing, the right thing is being done.

I lost my mother-in-law and only saw the good things in her once the gaping hole that she left opened up violently behind here.

But then, as I have already pointed out, time – for her – had already snapped.

*

I thought I was going to be a great publisher. I studied with astonishing minds. Electronic publishing was on everyone’s lips. The future was ahead of me.

The future was ahead of us.

But, in time, the future also snapped.

It snapped for me and it snapped for my loved ones.

I have seen famous people describe a nervous breakdown. I shall not describe it here. It is too public a place and I am not a very public person. Or maybe I am but maybe this is no longer what I should do.

Suffice it to say that – once again – it was a fact that at the heart of the matter, at the centre of my soul, it was a head that broke down and brought me to the edge of despair. Despair is not always clearly so – and thus, here, it was to be the case. Perhaps the essence of a nervous breakdown actually lies in our inability to obviously perceive it. The world takes on a different flavour – but that flavour seems so real and absolutely tangible.

My breakdown involved me writing about Iraq and its lead-up. As I did this, I prepared my own internal battle of wills. I prepared my own killing-field.

Every morning I wrote. Every afternoon I posted. I was an early convert to the virtues of an interconnected world.

I believed the politicians when they said we had to make a difference.

I believed in invading the sovereignty of dictatorship.

How could I believe otherwise after the lessons of the Balkans? How could I believe otherwise after my beloved Croatia’s experience?

Coherence, above all.

Coherence is an evil thing. Coherence is anti-human. Coherence is an excuse not to follow a new idea. Coherence is a bond that ties us down to previous stupidities. Damn the coherent man or woman. Damn the coherent instinct in us all.

So what saved me? After all this, which, in fact, is nothing out of the ordinary, what served to rescue my soul?

At the heart of the matter lies my head. Our heads, our thoughts, are sword blades we balance tenderly on. They can serve to strike us down or reveal us; they can serve to hurt us or save us.

They can serve to attack us or defend us.

They are what makes us different from everything else.